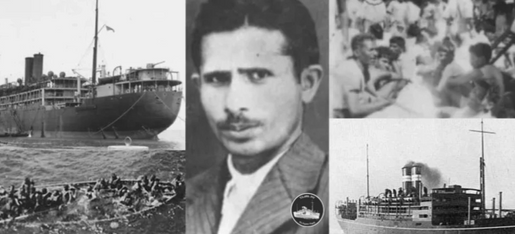

SS TILAWA 1942 | The Forgotten Tragedy | Nov 23 1942

What Happened to S.S. Tilawa?

The S.S. Tilawa Route

On the 23rd November in 1942, the SS Tilawa, transporting mostly Indian nationals en route to Mombasa, Maputo and Durban was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine near the Seychelles Islands. “I was one of the passengers on the board the Tilawa that night,” reads The Memoirs of Chunilal Navsaria (Survivor of The SS Tilawa). In his detailed account of the ship’s journey from Bombay (Mumbai), the author provides the type of narration that allows us to piece together the story of the demise of the SS Tilawa during World War II. Navsaria begins by recounting a train journey with his mother that began in his village in India and ended in the nation;s capital Bombay. He goes on to explain that the British India Steam Navigation Company’s (BI) usual fortnightly schedule was at the time reduced to only one voyage every six to eight weeks that led to a departure even more crowded and bustling than usual. “By now the pier was overcrowded with people,” his account continues. “The White and Indian police officers had a difficult task of controlling the huge crowd. There were so many passengers, friends and relatives trying to board the ship to say their good-byes, that police later had to stop them.”

“The ship carried 1st class, 2nd class and deck passengers. When I got on to the ship, I noticed there was hardly any room to move. I had a deck ticket and trying to find my bunk on the lower deck amongst all the confusion was a difficult task. My bunk quarter was next to a friendly newly married couple from my home town. My mother greeted and chit-chatted with them, asked them to take care of me and left the ship. After placing my trunk and bedding on the bunk, I went up to the upper deck to watch as the ship departed. At exactly the 17th hour, the ship set sail and left Bombay harbour. Once at sea, a boat drill was carried out and we were told not to light matches or torches on the upper deck. There was a blackout on the ship. The portholes were painted black and kept shut at night. There was a constant fear amongst passengers and crew of a (sic) enemy submarine attack. I made sure that I kept a life jacket close at hand.” Their trepidation during this wartime journey, it would tragically emerge, was well-founded. In 2001, the oldest known survivor of the SS Tilawa, Moulana Cassim Mahomed Sema, told his story to Kwazulu-Natal’s Sunday Times. “One night I heard a loud bang,” he recalled. “I instinctively knew it was a torpedo. I forgot my goods and my two companions who were sleeping nearby and rushed towards the lifeboats.” Sema, known to many as founder of the Muslim college Darul Ulum, Newcastle, was dressed only in pyjama pants and found himself in the cold night air jostling with other passengers trying to secure a safe passage off of the ship. “I could hear women and children screaming and my first thought was to pray. I managed to get into the third boat.” “There was chaos and panic among the passengers and Indian Crews (Khalasis) as they all headed to the upper boat saloon decks,” wrote Navsaria in his memoir. “Before I knew it, I was hurling down the stairs and injured myself. The ship’s Indian crew and deck passengers were all panic strickened. The chaos, hysteria and panic was causing the rescue operation to be hampered. While the launching operation of life boats were in process, I grabbed the rope holding the life boat which was almost halfway down, and slid into the boat. I injured myself even further in the process. The boat was half filled already, mostly with crew and a few passengers. The crew unhooked the boat and we fell free and drifted away slowly. “The time now was 02H00 on that bright moonlit night. I could clearly see the Tilawa’s lights and flare signal. With tearful eyes, I watched as the other frantic passengers stampeded into life boats, trying to lower them and save themselves from a terrible fate. I could hear their panicked screams and mournful tragic cries.” It’s likely that the fate of the SS Tilawa and its passengers were already sealed, but the vessel was still to be dealt another blow. “The ship, though it’s (sic) head had already sunk, was still afloat,” Navsaria told. “About half an hour later, while the frantic activities were still going on, a second torpedo exploded on the port side and within five minutes the Tilawa heeled over and sank. There were a loud noise and debris fell all around as the Tilwana was sinking.” “While we were on a lifeboat, there was another loud bang,” recalled Sema “and, within seconds, the Tilawa sank.” “The remaining passengers and crew either jumped or were thrown overboard and hysterically made for rafts or boats,” wrote Navsaria. “Others were too scared and shocked to move, and sank with the ship.”

At around this time Navsaria later learnt, first radio officer Mr. E.B. Duncan would have been transmitting SOS messages – the last of which broke off abruptly as he went down with his ship. In what Navsaria viewed to be a gallant sacrifice, Duncan lost his life putting out the call that would bring help to the Tilawa’s survivors. The cruiser HMS Birmingham was on its way to their rescue, though they could not know this yet. “There was a barrel of drinking water and biscuits on the life boat, but this obviously did not last long,” Navsaria recalled. Sema had similarly vivid memories of the rations that sustained him and his fellow lifeboat passengers: “We broke open a box that we found on the lifeboat and discovered some round biscuits. We found water in an aluminium container.” While these bare essentials kept him clinging to life, there were times when it seemed how doubtful how long he could endure: vomiting, weak and cold in the occasional rain, he didn’t imagine that he would make it to shore. “Arguments arose between the crew as to which direction to follow. The tension among all of us was rising. We drifted for an entire day and night,” recounts Navsaria of his boat’s own trials. “The sea was choppy and a cold wind was blowing. All I had to keep me warm was the pajamas (sic) I was wearing. During the day, rain came and the sea developed a considerable swell, tossing our life boat perilously. “On the morning of 25th November, we sighted a small plane (swordfish) that was approaching and signaling (sic) us. Later we saw a ship on the horizon, coming closer and closer. It was the HMS Birmingham that had come to rescue us. The medical staff of the HMS Birmingham worked extremely well.”

After being picked up and taken aboard the HMS Birmingham, survivors were provided with blankets and food, while the ship’s medical staff had their work cut out for them attending to major and minor operations as well as cases of burns, abrasions and shock. The HMS Birmingham rescued 678 survivors and the next day, the P&O shipping company’s SS Carthage rescued another four Indian seamen from the ocean. Navsaria noted that passengers were accommodated as follows, and commented that “Goanese stewards from Tilawa assisted in the pantries and were very helpful.”: White men: ward room, gun room Warrant officers: mess and cabins White women and children: Captain’s day and sleeping cabins Tilawa crew: in the waist Indian women and children: in admirals’ day and dining cabins Deck passengers (men): on hangar deck and starboard hangar The HMS Birmingham returned its passengers to Bombay, berthing at Ballard pier on Friday, 27 November 1942 to a reception of relatives and friends inquiring after their loved ones, alongside tables laid with refreshments and warm, clean clothes. For those waiting, news would bring either heartbreak or a flood of relief. For those returning, life would never be quite the same with the memories of their ordeal and of the friends and relatives they had lost. The devastation the sinking of the Tilawa wreaked on the lives of survivors and descendants of those who perished, continue decades later. And the mystery as to why the Tilawa was sunk remains unanswered to this day. Surviving passengers witnessed friends, family, and fellow countrymen drown in terrifying circumstances. Survivors enduring barracuda attacks through the night. Anguished cries for loved ones. Those who lived would go on to tell their stories of the lives lost and the horrors seen, so that history may be preserved. Descendants left to live a life of poverty. Children orphaned as a result of what some argue to be a war crime.

A tragedy that cost the lives of hundreds of Indian people

TILAWA 1942™ | The Forgotten Tragedy™

Dedicated to the missing & surviving victims of the SS Tilawa tragedy.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.